Patent Theory is always improving the algorithm. However, the following are some tips related to getting the most out of the system now.

A Guide to Drafting Patent Claims for the Novice Claim Drafter

Patent Theory, July 24, 2020

Patent claims are the metes and bounds of your intellectual property. The rest of the patent application including the figures are there to support your claims. Therefore, the claims are the most important part of the entire patent application. No pressure, but the more you practice writing patent claims, the better you will get at protecting your invention.

To understand how to begin, it is useful to understand how your patent claims will be interpreted by the patent examiner. An examiner is supposed to look at the patent claims “as a whole” rather than individual parts. That being said, your claims will often be compared, in parts, to different prior art references in a rejection based on “obviousness” in the U.S., or a lack of “inventive step” in Europe.

This is important when considering how to start your claims, and what to claim as your “independent claim.” The independent claim is the umbrella under which all of your “dependent claims” will logically reside. The independent claim is, therefore, the most important one to consider. It needs to be broad enough to cover implementations that are a design-around from any given implementation that you have considered and explained in your patent application, but narrow enough not to read on prior art.

Identifying Your Point of Novelty: The Line Between Your Innovation and the Prior Art.

Next, let’s take a look at the identifying the point of novelty for the independent claim(s). The independent claim is what you will need, as a bare minimum, to prove that a competitor infringed on your product. This means that you should avoid thinking about claiming what results the invention can produce and instead think about the way in which it achieves a given result and write those steps down. After you have written those steps down, try and broaden up the steps by looking at each of the words and phrases, and asking yourself “Is this required to overcome the prior art, or is there a broader word that we can use?”

For an example in drafting your claims too narrowly, say you want to patent a field programmable gate array (FPGA). If you draft your patent claims overly-narrow to simply cover the way an FPGA works, your competitors may read your published patent application, and change just one element in your independent claim to create a slightly modified FPGA-like device that doesn’t infringe on your independent claim.

At the same time, as an example of drafting an overly-broad example, let’s stick with the FPGA example. If you draft your claims so broad to simply refer to the FPGA invention that you want to protect as simply “a switch” with nothing further to limit your claims to avoid reading on the prior art, you won’t likely end up with an allowable patent application as everything “switch-like” will be used by the patent office to reject your application.

Let’s look at a real-world example. Say you were Larry Page from Google, wanting to patent your new method of ranking search results. Let’s consider how this patent claim may have started. It may have started more like this:

1. A method for scoring a bunch of search results, comprising:

counting citations of any of the web pages in the search results.

Since Larry knows that citation counting was already in the prior art, he knows this claim is over-broad. As described in this patent, “the present method is more subtle and complex than citation counting and gives far superior results.” More specifically, this patent itself states:

Like the citation rank, this definition yields a page rank that increases as the number of backlinks increases. But the present method considers a citation from a highly ranked backlink as more important than a citation from a lowly ranked backlink (provided both citations come from backlink documents that have an equal number of forward links). In the present invention, it is possible, therefore, for a document with only one backlink (from a very highly ranked page) to have a higher rank than another document with many backlinks (from very low ranked pages). This is not the case with simple citation ranking.

However, as mentioned, while it may be useful to discuss the results in the Detailed Description, it shouldn’t be in the claims. So, Larry may have been tempted to create a second version of the independent claim to look like this:

1. A method for scoring a bunch of search results, comprising:

performing an internet search using a search engine;

providing the search results including improved search results when compared to basic citation counting search ranking.

Do you see the issue with the claims above? They claim results which don’t provide the metes and bounds of the invention, it doesn’t describe how the search result ranking is improved. A third attempt may have looked like this:

1. A method of scoring search results, comprising:

selecting an initial N-dimensional vector p0;

computing an approximation pn to a steady-state probability p∞ in accordance with the equation pn=Anp0;

determining a rank r[k] for node k from a kth component of pn.

What do you think of this claim? It definitely doesn’t read on the prior art of general citation-based search ranking, right? However, it is probably too specific, and should really only be left as support in the specification of the application for a broader independent claim. Moreover, including equations in most claims is rarely necessary, and often detrimental. Instead, try to describe the concept behind the math. Such a claim might be:

1. A computer-implemented method of scoring a plurality of linked documents, comprising:

obtaining a plurality of documents, at least some of the documents being linked documents, at least some of the documents being linking documents, and at least some of the documents being both linked documents and linking documents, each of the linked documents being pointed to by a link in one or more of the linking documents;

assigning a score to each of the linked documents based on scores of the one or more linking documents and

processing the linked documents according to their scores.

This claim is in fact what was allowed. Can you see how this claim was generalized to capture the novel concept of what Larry wanted to cover, without being too narrow, and without being overly broad? You may have also noticed that this claim has a longer preamble, which of course isn’t preferred, and is trending out of practice, but the rest of the claim is generalized to cover implementations that don’t exactly require”[an] N-dimensional vector p0,” “an approximation pn to a steady-state probability,” or “a rank r[k] for node k from a kth component of pn.” These terms are altogether too limiting, and more the point, harder for both the Examiner and the jury to understand.

Say you have come up with some sort of software that saves time. Often, an inventor will want their patent claim to cover the results of the invention. The trouble here is that results, while in some cases can be beneficial, a patent claim usually needs to focus on how a result is generated, rather than the result itself.

As an example, an inventor may have come up with a method of producing a part that will reduce the cost of producing the part. It would be a mistake to claim, especially in the independent claim, for example: “A method, comprising: ... reducing the costs of producing the part.” While you could use this element in a dependent claim, and you should include this statement as an advantage of your invention in the Detailed Description section, leave it out of the independent claim. The reason is, do you really want to require a competitor to reduce costs in order to infringe on your product?

What Should Be Included in the Preamble?

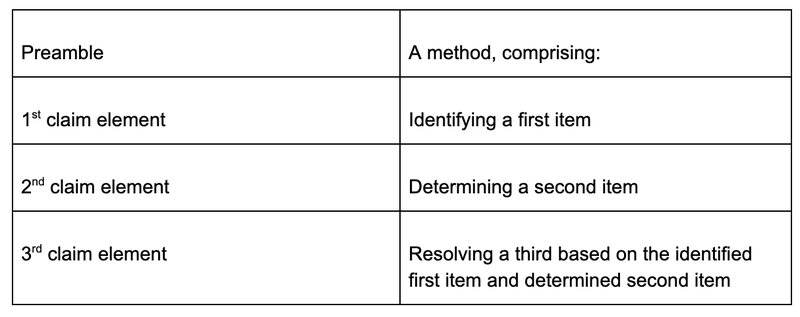

Switching gears now, lets take a look at the structure of a patent claim. A patent claim starts with a clause that is called the “preamble.” Then, the claim will recite elements, as shown in the example below:

In the U.S., the preamble is not supposed to have any patentable weight. This can be both a blessing and a curse. Sometimes a patent practitioner will add language to the preamble in an effort to overcome prior art. While sometimes this works, as an Examiner may ignore the fact that the preamble isn’t supposed to have any patentable weight and allow the application, when it comes to defend your patent in a court of law, a lengthy preamble can cause problems. The best practice is to keep your preamble short. In fact, the trend in patent drafting has trended towards leaving the preambles as generic as possible, i.e., “A method, comprising:”, “An apparatus, comprising:”, “A system, comprising” as opposed to “A method for connecting two networks within a range of wireless compatibility, comprising:”, “A cellular phone for wireless communication to a base station,” etc.

All of these specifics in the latter claim preamble examples can be provided as examples in the rest of your patent application, and Patent Theory can help provide that boilerplate. This isn’t to say that sometimes these narrower and more specific claims can’t be useful, but the best practice is usually to start from the broader level of claiming more generically. This is also a good place to start in view of the discussion above related to claiming either overly broad vs. overly narrow. As the preamble isn’t supposed to have any patentable weight, why not start generically.

What Should I Include as Dependent Claims

Dependent claims, as the name suggests, fall under the umbrella of a related independent claim. Dependent claims are generally used to flesh out the independent claims further and are often viewed as back-up plans in view of the plethora of prior art that may be cited against your patent application. In that regard, it is useful to include some dependent claims that might help overcome the prior art that you know of. So, once you have drafted your independent claim, try and come up with more specific examples that more narrowly define your invention than what was included in the independent claim.

As an example of a dependent claim, let’s take a look at the previous independent claim for Larry’s improved search engine.

1. A computer-implemented method of scoring a plurality of linked documents, comprising:

obtaining a plurality of documents, at least some of the documents being linked documents, at least some of the documents being linking documents, and at least some of the documents being both linked documents and linking documents, each of the linked documents being pointed to by a link in one or more of the linking documents;

assigning a score to each of the linked documents based on scores of the one or more linking documents and

processing the linked documents according to their scores.

You may look at this and think, let’s describe the typical use-case of this invention, such as being used as a consumer searches google. So, you might write:

2. The computer-implemented method of claim 1, wherein the method is carried out on a general-purpose computer.

The issue with this claim is that it is almost a given that this method will be carried out by a general-purpose computer. Instead, it may be useful to think through who is the most likely infringer. To start, you don’t want to write a claim that captures infringement by a consumer because 1) consumer’s aren’t typically wealthy enough to make patent infringement suits against them very worthwhile and 2) what you’d really like to cover are your competitors. So, what would your competitor be doing? Perhaps you could write a claim that covers their/your implementation such as:

2. The computer-implemented method of claim 1, wherein the method is performed by one or more servers that are remote to a client device.

This claim tries to capture the implementation of how a competitor might implement the invention. Another thing to consider is further definition for each of your independent claim elements. For example:

3. The computer-implemented method of claim 1, wherein the assigning comprises weighting the score based on … xyz.

This type of dependent claim is useful to further define the steps of the independent claim, and may be used to define your invention away from the prior art.